November 4, 2024

LEARN’s Kerry Hoops Uses Assent-Based Practice to Make COVID-19 Vaccination Comfortable for Kids with Autism

FEATURED POSTS

October 14, 2024

October 7, 2024

October 7, 2024

By: Katherine Johnson, M.S., BCBA

Senior Director of Partnerships, LEARN Behavioral

Vaccination visits can be terrifying for an autistic child – a new environment, unfamiliar sounds and smells, being touched by a stranger, and all of this culminating in a painful poke. Anxiety and unwillingness to sit for a vaccine shot can lead to parents and medical professionals winding up with a difficult decision: hold the child down against their will or forego the vaccine. At LEARN, we care about our clients’ health and the experience they have when receiving healthcare.

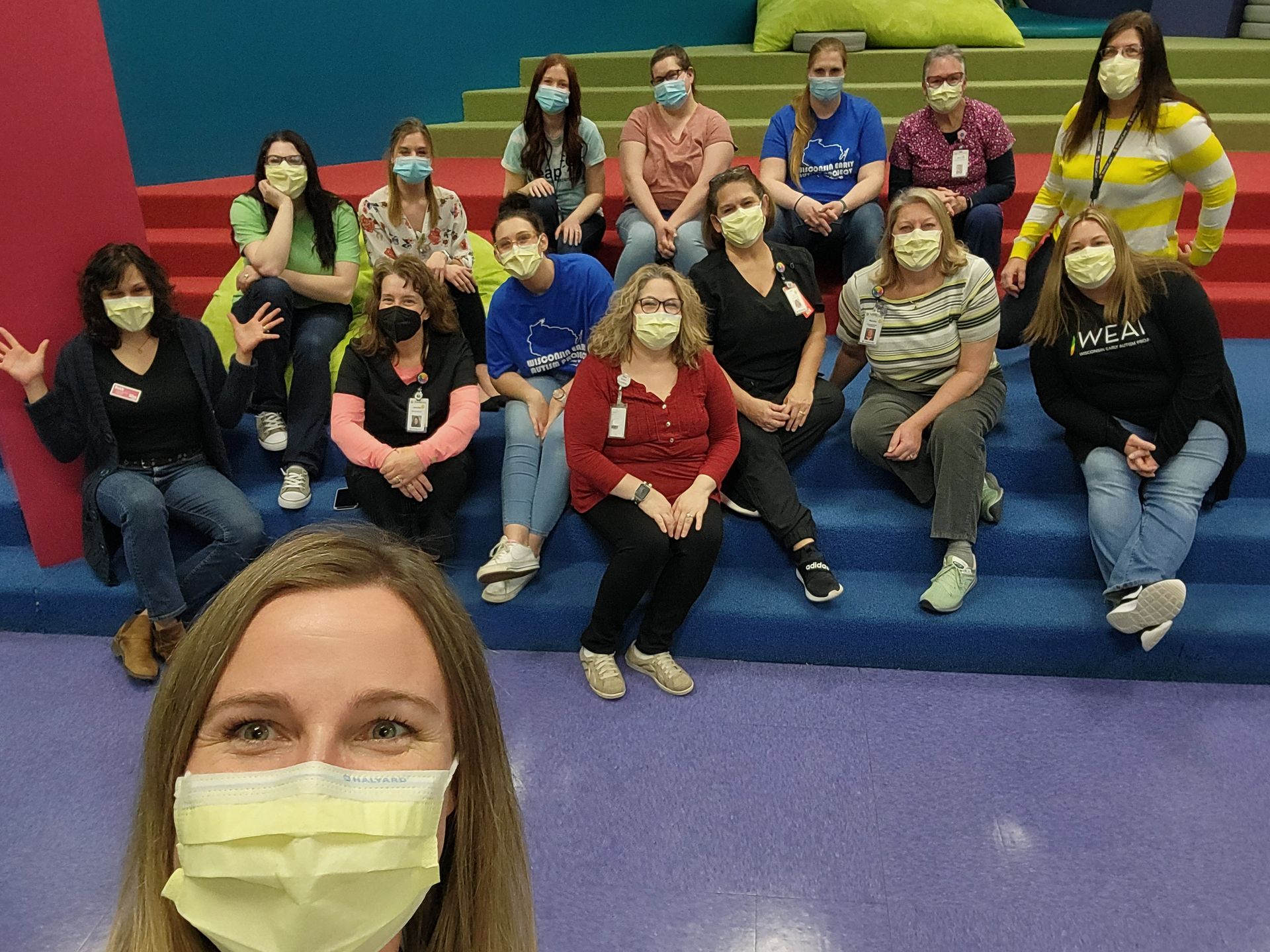

Recently, the Wisconsin Early Autism Project (WEAP, a LEARN organization) partnered with the Autism Society of Greater Wisconsin in a series of vaccine clinics. These events were carefully designed to provide families with autistic children a positive experience while receiving their COVID-19 vaccines.

The clinics were held in a local children’s museum, and a pair of seasoned clinicians teamed up with each child, who had reviewed a vaccination social story before coming. Parents answered a questionnaire about their child’s experience with shots and specific interests in advance; clinicians used this information to build rapport with the child, make them comfortable, and provide distraction. Choice was built into the entire experience: children got to select toys, the type of bandage they received, and the body part where they would receive the shot. Clinicians also provided non-invasive devices to mitigate injection pain, like the Buzzy pain blocker, and shot blockers. The most intriguing part? Clinicians waited until the child indicated they were ready before giving them the vaccination.

The result was phenomenal: dozens of autistic children receiving their COVID-19 vaccine without a tear. Kerry Hoops, our Clinical Director at WEAP, said that one experience in particular stood out to her: a boy who was terrified that the shot would hurt, asking about it repeatedly. After assuring him they would not let the shot be a surprise, they spent some time doing one of his favorite activities: having races around the museum. They gave him the opportunity to watch his mother get the vaccine, and then took him to a sensory room in the facility where they watched wrestling (WWE) together. Getting him comfortable was a process that took nearly an hour, but the end result was a child who received his vaccine willingly, and left having had a positive experience. “The coolest thing is seeing the parents’ responses,” said Hoops. “They were so happy because they were not expecting the vaccination experience to go as well as it did.”

The procedures Hoops and our other clinicians at LEARN used are all evidence-based practices commonly used in applied behavior analysis (ABA) called “antecedent interventions.” Frequently, interfering behaviors (like screaming or bolting from a doctor) occur because the child is trying to escape from something uncomfortable or scary. Antecedent interventions are meant to create an environment that the child doesn’t want to escape from. “We’re trying to create a positive experience so when they go in for their next vaccine, they’re not going to be afraid,” says Hoops.

The most groundbreaking component of these vaccine clinics was it was not the medical professional who decided when it was time for the shot, nor was it the parent. It was the child. In addition to using antecedent interventions, our WEAP clinicians also had the medical professionals hold off on the procedure itself until the child had indicated they were willing to receive the vaccine – something known as “gaining assent.”

Assent, having a pediatric patient agree to treatment, is a practice that has been required for medical research since 1977, citing the need to respect children as individuals. Since then, some practitioners have extended assent procedures to their regular pediatric practice, asking for the child’s permission before they listen to their heart, for instance. The new BACB ethics code includes a provision for “gaining assent when applicable,” and proponents argue that Assent-Based ABA prevents difficult behavior and teaches children critical self-advocacy skills. The ability to determine what is and is not comfortable and acceptable for oneself is particularly important for children who struggle to use language, or who are at higher risk of being misunderstood because they are autistic. At LEARN, Assent-Based Programming is one part of our overall Person-Centered ABA Initiative.

Although Assent-Based practice doesn’t guarantee that every child will eventually agree to the procedure (2 children of the 73 children in the clinic did not assent to the vaccine), it was overwhelmingly successful. The impact was evident in the enthusiastic responses from parents afterward. One parent wrote, “Thank you for the BEST vaccination experience ever! Our family was overjoyed to have been part of this clinic.”

LEARN is proud to announce that WEAP and ASGW are planning on expanding their vaccine clinics to regular children’s vaccines in the coming year. For more information, check out the ASGW’s website.

Kerry Hoops, MA, BCBA, is the clinical director for Wisconsin Early Autism Project’s Green Bay region. Kerry began her career helping children with autism over 20 years ago when she was attending UWGB for her bachelor’s in psychology and human development. She fell in love with the job and chose to work in the field of autism as her career. Kerry furthered her education at the Florida Institute of Technology and Ball State University with a master’s in applied behavior analysis and became a board certified behavior analyst (BCBA). She loves helping children and families in Wisconsin and internationally in Malaysia. Kerry also works at the Greater Green Bay YMCA for the DREAM program, focusing on events for socialization for adults with special needs. She has been on the board of directors for the Autism Society of Greater Wisconsin since 2014 and is the acting president.

LEARN more about LEARN’s Person-Centered ABA Initiative. And, to stay connected, join our newsletter.